Invisible friends in the air we breathe?

By Jake Robinson

The air we breathe is teeming with life.

Scientists have studied what exists in the air for many decades. There’s even a special term to describe airborne particles originating from living organisms – bioaerosols. These particles include bacteria, viruses, fungi and other microbes, but also pollen, spores and other plant and animal cells.

They sail through the air and are mostly invisible, and we inhale these unseen trinkets of complexity in the millions each day.

We literally breathe in life.

James Nestor wrote in his book Breathe that with each breath, we inhale more air molecules than there are grains of sand on all the world’s beaches. This equates to up to 15,000 litres of air daily. Breathing exposes our walking ecosystems to an array of invisible biodiversity, which triggers an intricate cellular dance deep within the caverns and tissues of our bodies. This cellular dance shapes our health and behaviour.

It has been known for a while that bioaerosols can affect human health. Yet most of the research in this area has focused on understanding and preventing ‘unhealthy’ human exposures to pathogens and allergens.

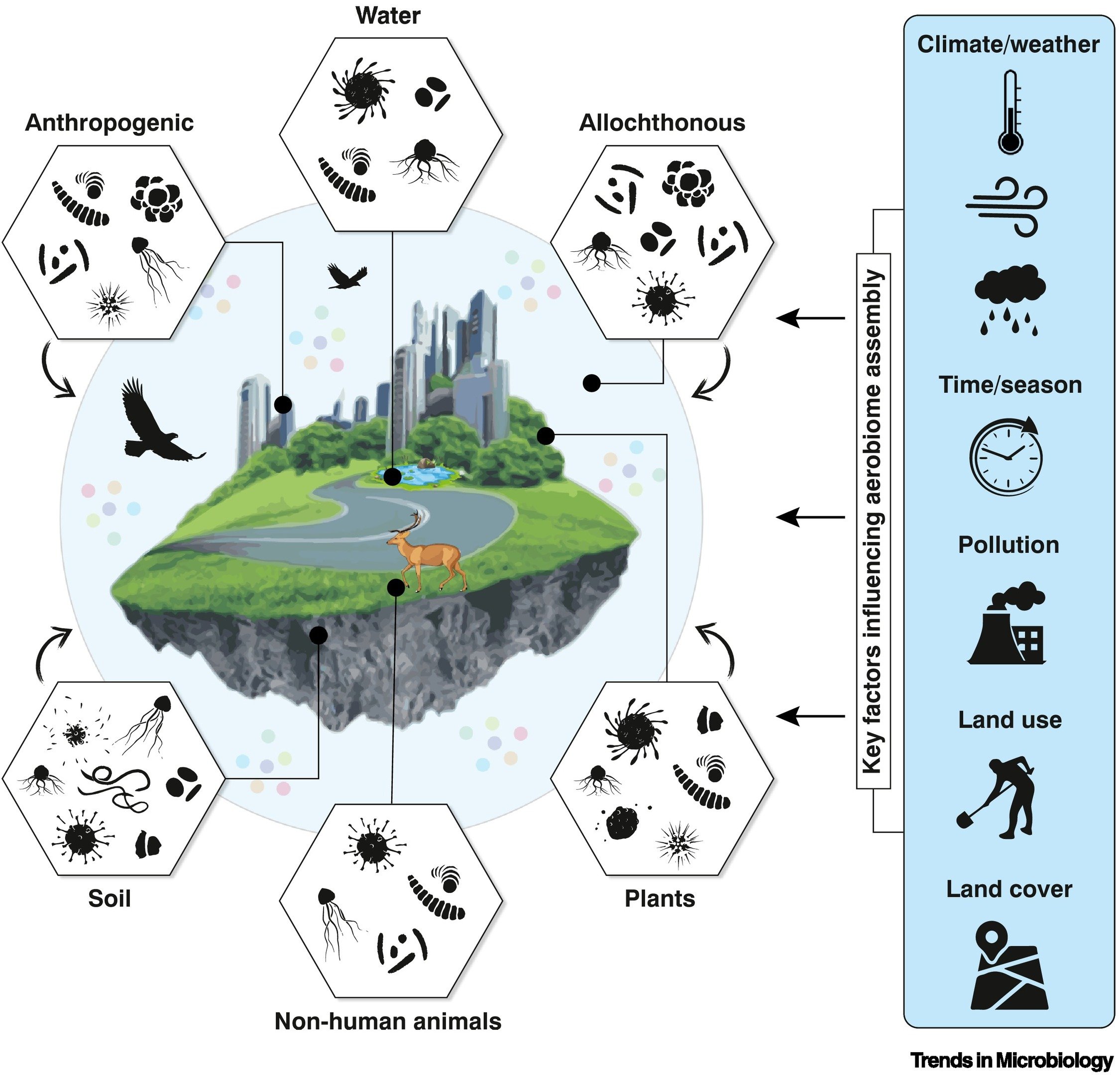

However, as we discuss in our new paper published in Trends in Microbiology, there has been a recent paradigm shift in thinking about bioaerosols. Exposure to a diverse assemblage of microbes in the air or the aerobiome, and other substances, such as phytoncides (compounds in plant-based oils), may have important health benefits. Our invisible friends in the soils, plants, and air provide critical roles in regulating our immune systems and many other functions in our bodies.

It's a tantalising tale of missed opportunities, for our fixation on pathogens has long overshadowed the potential of these benevolent bugs.

Now one of the challenges - but also opportunities - is working out exactly what ‘healthy air’ is.

We also need to develop strategies to design and restore our environments to optimise exposure to the ‘good bugs’ and reduce our exposure to the ‘baddies’, including the pollutants and allergens that wreak havoc on our bodies.

But there’s good news! Our research shows that by restoring ecosystems and vegetation complexity to more natural states, we can increase the diversity of microbes in the air and potentially reduce the abundance of pathogens. Restoring vegetation can act as a powerful shield against the insidious grip of pollution. However, we must tackle the source of pollution as a priority.

This paradigm shift in thinking about some bioaerosols being ‘health-promoting’ opens new and exciting research avenues that could enhance human and environmental health.

The paper Aerobiome-health axis: A paradigm shift in bioaerosol thinking was published in Trends in Microbiology.

To read more about the invisible friends in the air, check out Robinson’s new book Invisible Friends: How Microbes Shape Our Lives and the World Around Us.

For more information on a cutting-edge initiative aiming to define ‘healthy air’ and incorporate this new aerobiome knowledge into public health strategies, check out BioAirNet: https://bioairnet.co.uk/